Many serious game designers are eager to stuff a game with mechanics and information, often forgetting that there is more to game design than the knowledge we want players to acquire. When focusing only on the “serious” part of a serious game and trying to fit as much in the game as we can, we cannot forget that there is a whole other world to the “game”.

Learning outcomes are not only dependant on the idea behind the game but also on the principles of game design incorporated into the design process. Modern game designers are making the best out of it.

For example, Papers, Please, one of the socially conscious indie games that gathered a lot of attention for giving players a glimpse into a life under communist dictatorship, was often praised for immersive storytelling and ”incredibly minimal, strikingly stark art and sound design”. The design was part of the experience where “[it] does an excellent job of bringing Arstotzka to life – in a suffocatingly uncomfortable sort of way” and adds another layer to the in-game world. This immersive aspect of the game is why mainstream games are very often seen as more compelling than their “serious” counterparts.

Thankfully, there are plenty of studios, designers, and creators that take on serious issues with more design-oriented attitude. And people from the serious games industry are starting to notice that good graphic design and storytelling are aiding player’s learning circle.

Looking at the final projects of the MGIEP Gaming Challenge, the people behind this particular contest also noticed the importance of the factors mentioned above. We already wrote extensive texts about the World Rescue and even talked with Sandhya Nankani from Literary Safari about how this children-friendly and accessible game came to be.

Now we took an opportunity to talk with the We Are Müesli game studio team, Claudia Molinari-Ivanović and Matteo Pozzi, co-authors of Once Upon A Tile (shortened as OUT)—a finalist in the MGIEP Gaming Challenge.

OUT has been developed in cooperation with Daniele Giardini and Pietro Polsinelli. Daniele Giardini is an artist and founder of now-closed Holoville and DEMIGIANT. While living in (how he describes it himself) a supersecret hidden cave between Rome (Italy) and Niš (Serbia), he is dealing with game design, coding and storytelling, art,unity assets, comics and interactive stuff, projects for museums/exhibitions, apps and websites, and a lot more. Meanwhile Pietro Polsinelli, a member of Suppagumma ensemble, is a game designer and developer mostly working on applied (a.k.a. educational) games.

Once Upon A Tile creative team is a prime example of a group of people that has it all to create a really immersive sustainability game—a great sense of graphic design and ability to tell any story in a way that sucks a player into the game. The stories they explore through games, be it history, art or human wellbeing and sustainable development, are consistent and immersive. We asked Claudia and Matteo about their designing process and how it was affected by the MGIEP Gaming Challenge.

Many of your games dive into serious topics related to the culture, society and its problems. What is important for you in choosing projects?

We leverage the videogame medium to explore unconventional themes and stories that, for different reasons, could sound unpopular, be forgotten, or just never be explored by means of a game – like, for instance, Italian Resistance against Nazi-Fascism in “Venti Mesi“, a topic we feel still urgent today, but too often relegated as something “distant in the past”, or “The Great Palermo”, a free interactive ballad about street food, folklore and culture of the city of Palermo, Sicily, or “SIHEYUAN”, a cooperative action-puzzle game for 4 players of all ages and types, conceived as a multiplayer variation on classic falling-block mechanics and inspired by the architectural tradition of “siheyuan”, historical courtyards of Beijing, China. We actively try to produce inclusive and meaningful experiences focused on such cultural and empathic themes, basing them on the three main pillars: storytelling (narrative games), design (simple, intuitive, visually stylish and interactive) and collaboration (including partners and players from outside the traditional “gaming” boundaries).

Why and how, in your opinion, can a game serve as a tool to talk about these topics?

We believe in the power of good design. A great design experience, being a product or a service or an advertisement campaign, is more than just a communication tool: its purpose it to create a memory, something that stays in time. Our approach to video games is rooted in the Italian tradition of design: we see games as digital artefacts to bring meaningfulness, culture and beauty to the global market.

The artwork in all of your games is quite simple but very eye-catching. How important are the visual aspects in the process of conveying a game’s message to the players?

The art style in our work varies according to its purpose. Our projects can be considered experimental. So is their art. Working with a design approach in mind, the art style must serve the objective of the game. That is why it is always different but still interconnected across all the games. In the majority of the cases, players will grasp less than half of the reasons why the game has been designed in that shape, but designing speaking everything has a reason to exist, everything has a meaning, being colours chosen or overall composition.

What are, for you, the main challenges of designing games?

There are many different challenges when making a game. Understanding how to convey an “important” message through the game mechanics’ logic, for example, but also finding possible working partners from outside the game industry or scene, people who work in foundations, city councils, museums, tourism and historical archives and who never thought about adopting a video game to promote their content. In the case of OUT our creative solution was to adopt a plurality of points of view on the topic, trying to tell multiple short interactive stories (hence engaging possible multiple audiences) instead of dealing with the issues from a single perspective.

Speaking about the game Once Upon A Tile—What is it about? How does it work?

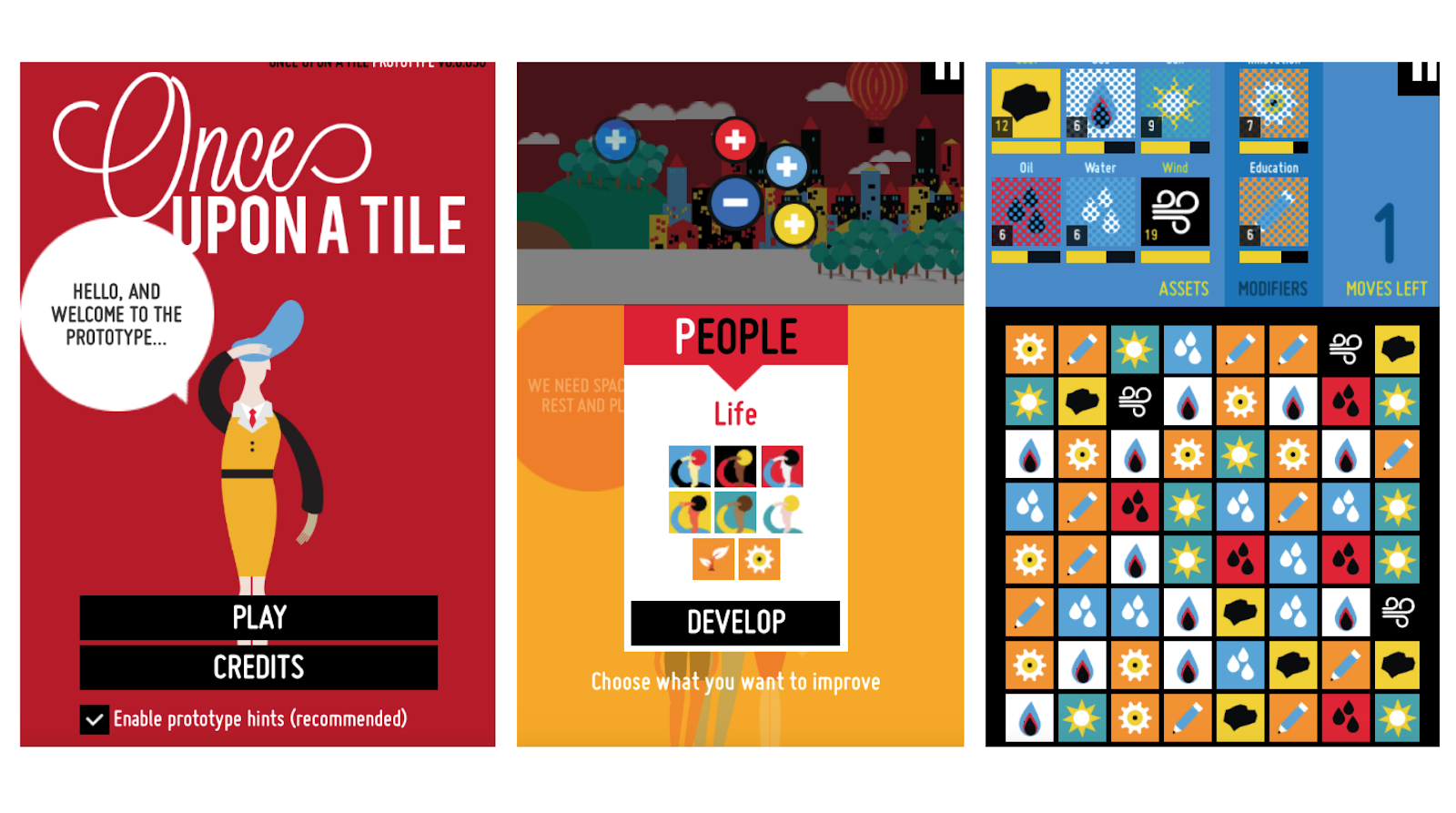

“Once Upon a Tile” is a prototype for a mobile game about peace and sustainable development where players manage an evolving world by matching resource tiles and generating new results and products. The game board is divided into two main parts: an upper part (“life on the surface”) and a lower one (the “generative underground”). The surface is inhabited by little human beings, as in a “life simulation game” à la Sims (or Little Computer People). The underground is filled with matchable tiles (as in casual puzzle games like Candy Crush) that represent resources for human activities, either tangible or intangible. The player’s goal is to evolve and preserve life and universal wellbeing on the surface (from the establishment of buildings to the development of social relationships) by generating appropriate elements in the underground and dealing with the complex consequences of her/his actions. For example, matching three coal tiles in the underground lights up a fire on the surface that keeps humans heated, but also produces pollution. And of course, matching coal tiles also makes them rarer… The game has a simple structure but players are required to think carefully about their matches.

Why did you take an interest in creating a game about peace and sustainable development? What was your starting point in the designing process?

Our proposal was to create a game that leverages the wide reach of casual mobile games to ease the approach to the theme of sustainable development and its social consequences. The game, in fact, comprises classic tile-matching mechanics feeding an evolving world simulation: a casual game that narrates an important story our generation has the responsibility to narrate, the story of a peaceful and sustainable future for all. Hence the ironic title, Once Upon a Tile (OUT). With OUT we wanted to surprise the player by applying simple and highly-engaging “match-three” puzzle mechanics to the complex emergent generation of a “better world” within the game itself. The resulting hybrid genre may be called a “puzzle life-simulation” game.

How did you get involved in the UNESCO Gaming Challenge? Did this experience change anything in the way you look at games, yourself and our world?

When we saw the UNESCO MGIEP Gaming Challenge we were surprised to finally see a big corporation getting closer to the video game industry, not just like to make an entertaining game and promote their mission, but mostly to use it like a communication and social tool to change human behaviours. We found ourselves pretty close to this view as, before this challenge, we had the chance to work on other projects with similar missions (being cultural or artistic ones), and work with other people that share our gaming values. In fact, OUT has been developed in collaboration with other two amazing developers: Pietro Polsinelli, a developer with 25 years of experience in modelling and application development for corporations and institutions. As a game designer and developer he works mainly in applied games in the fields of health, social impact, education for the European Union, universities and research centres; and Daniele Giardini, a programmer, designer, artist and writer, with 15+ years of experience with digital applications for institutions, museums, exhibitions, movies and TV shows. As a game developer, he worked on more than a dozen of games, won various independent awards, is featured on Steam, and developed some widely popular plugins for the Unity engine (HOTween/DOTween).

Was there any particular reason for choosing a mobile platform for this project?

The game was initially designed for smartphones, with an adaptive layout that makes it playable also on tablets and desktops, so to reach the largest possible audience. The reason behind it is linked to the fact that we wanted to spread the sustainable development goals as much as possible to Western Society. This could be achieved by using a worldwide technology. This was an opportunity not to miss, from a psychological and social perspective, use a tool of consumption with a casual mechanic to divulge a vital topic.

Let’s talk about playing the game OUT—What skills are needed?

No special requirements are needed to play OUT: you just need a smart device. We intentionally designed the game to be as accessible as possible to a variety of audience.

What, in your opinion, can be learned from playing the game? What would you like players to learn from it or experience through it?

We conceive OUT’s player as a “learner as producer” [Gee, 2013]: The core of the gameplay tells a story of the relationship between resources, production, growth, knowledge and communities, and how the story ends is partially constructed by the user, not in a book-like linear way. In other words, OUT was not designed as an “educational game” in the traditional, sometimes pejorative, sense; it was designed as a game to be played, and what it teaches is built in the gameplay experience, not as a secondary narrative. An instrument where different themes can be “played” [Devlin, 2013], a tool of “situated learning” through exploration and experience: this is the design goal we wanted to reach with OUT. We think the real learning challenge we wanted to undertake was to design a meaningful connection between becoming a proficient player and getting a functional grasp of the concept referred to by the game [Koster, 2013].

What do you think are advantages of game-based learning?

Game-based learning is defined by nature as lessons which can be competitive, interactive, and allow the learner to have fun while gaining knowledge. With OUT, we designed the game covering 7 learning steps: learning the matching logic and its immediate effect of generating products of different kinds; learning about the effects of such products on the simulated community; learning about the community’s dynamics in different contexts of abundance vs scarcity; at critical in-game moments, discovering actual points of contact with the real world, potentially connected with contextual content of UNESCO MGIEP‘s real initiatives and/or in-app donations to real projects; learning about the intra-community (i.e. social) dynamics, the emergence of diversity, the spectrum of possibilities; via gameplay repetition, developing familiarity with the diverse situations and effects of her/his choices. In particular, gameplay that leads the simulated community to thrive or towards extinction should induce a transformative process that makes the player more aware of diversity, context and relationship between seemingly-unrelated causes and effects; experiencing the complexity and superficially- unexpected consequences. This model was shaped to affect the player’s sensitivity towards the whole set of peace and sustainable development issues.

Can games promote sustainability? If so, how?

Games are a great medium to promote anything. They have two huge drivers: immersivity and identification. With the right storytelling and gameplay, everything can become an experience of growth. What is missing are big corporations and institutions willing to invest budgets to this new forms of interactivity. The majority uses contest programs (OUT was developed thanks to one of those) with restrictions and winning criteria that, at times, can kill more sophisticated ideas.

Our final, more personal question: If you had to choose one favourite game with serious topic, what would it be?

The questions were answered with the contribution from Daniele Giardini and Pietro Polsinelli.

How did you like this post? Let us know in the comment section or on our social media!

You can also fill this short survey to help us create better contentent for you!

For more games about Life below water-related issues visit our Blog and Gamepedia!